Sanctae 2012-14

Sanctae is a photographic installation of 21 larger than life (8ft x 3ft) secular saints, each adorned with their own hand gilded gold leaf halo.

Download the artist’s statement on Sanctae (PDF).

Interviews and background – a short film by Joanna Ensum

Virtual tour of the installation

Lion Art Projects – see review by Mila Lewis ‘The most important exhibition you may never see’

Sanctae – Secular Saints (text by Tiff Oben)

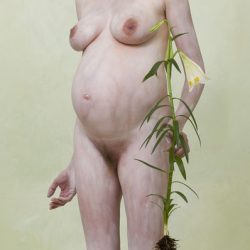

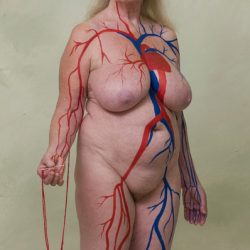

Sanctae, the installation by artist Ione Rucquoi, consists of a large architectural enclosure that creates an inner space inhabited by photographic images of golden-haloed, naked female subjects. Byzantine in their elevated remoteness, resonant with Catholic symbols and signs, these idols are large in scale and larger than life as they encircle the viewer and look down upon us, fixing us with exacting gazes. Within their company, and within the shrine-like, womb-like structure that houses them, I feel I must almost avert mine eyes and can initially, only shyly, return their penetrative stares. I sense what it is to be a lesser being in the presence of the saintly, so bathed are they in difference and otherness to my earthy humanity.

Despite the certainty that I know each individual for their mythologized suffering and piety, Rucquoi’s installation houses photographic images of women as real as any of us. Where the holy remain beauteous despite earthly torments Rucquoi’s secular assembly bear the scars and stark stares and full burden of the tormented. For these are not icons, not archetypes, but portraits of individual women, each marked by their corporeal experience and presence upon this earth.

Sanctae’s subjects are formed by Rucquoi’s reading of the concept of the Shadow developed by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (1875-1961). For Jung the Shadow denotes the dark side of humanity, a side that is denied recognition by the ego and so remain buried deep within the unconscious (1983, p.422). To unearth the Shadow and come to terms with it can be understood as a form of freedom, but freedom from what and to what effect is the Shadow unearthed?

If the ego is formed, contained and restrained by the male-biased Symbolic order and works to perpetuate the patriarchal law of the phallus, then it is such laws that bury the Shadow within from the very beginning? The Symbolic order abides within and upon our very bodies, its laws are covetous with lust and death and shamefulness and carnally dominated by the sins of the flesh. These sins are marked upon Rucquoi’s subjects, as manifest upon the flesh as the black carrion that hangs from the neck of one of Sanctae’s inhabitants.

Could it then be that to unearth the Shadow is to overcome the Symbolic? Could it be that to come to terms with the Shadow, to wear the Shadow upon the flesh rather than bury it within is to enable an existence, a state of being based upon the pre-Symbolic, a time of freedom and un-encumbrance by patriarchal values? Is Rucquoi’s personification of the Shadow synonymous with an overcoming of patriarchal rule?

The images represent the aspects of ourselves that society repudiates, aspects that, like the Shadow, are buried and remain hidden, refused representation until Rucquoi cast her lens upon them in recognition of their being. Within Sanctae, we become dazzled by the truly and utterly naked form of woman. In antithesis to the western tradition, Rucquoi does not cover her subjects in the eroticized decency of the idealized nude favoured by male-biased aesthetics. Like the Shadow, Sanctae exists beyond the controlling boundaries of hegemonic discourse, uncovering, glorifying and personifying naked and unruly biology upon the bodies of real women.

Small wonder then, that Sanctae upsets and unsettles for within its confines howls the Shadow of the female body, physically and conceptually, out of control. Within Sanctae there is no passive come-hither, porn-inspired, pubescent, hairless casts of sexually available femininity. Within Sanctae women ripen and age, within Sanctae women lose control of their bodies and live, within Sanctae women lose control of their bodies and die. Herein reside the farmer’s daughter with tit and pubic hair so long it cascades to the floor in dirty locks, herein resides veiled vestal with pendulous burdensome golden tits who are more than a mammary focal point for the male gaze, herein reside lactating holy mothers whose breasts are over-flowing and bounteous with the goodness of milk, herein lie in uttermost freedom the outcast mother of never-born children, herein reside women whose breasts, whose ovaries, whose wombs, whose every biological sign of womanhood have been removed. Clothed in bodily secretions and scars and wrinkles and excess fat and stretched skin; Sanctae sanctifies through the visualization of the graphic minutiae of biological trauma and the everyday facts of being woman in this world.

Sanctae offers sanctuary, a space where its subjects can be what they are without shame, where its subjects are beautiful and where they hold the power, where they welcome and confront the judgmental viewer with overbearing gaze, defying them not to be moved, not to fall to their knees in awe and wonder and pray for forgiveness for never having seen the beauty before.

Sanctae renders the unseeable seeable, the unsayable sayable, the buried uncovered, the inside outside; in Sanctae the hidden is made known. We cannot always bear what we discover within, but we must accept it as a reflection of ourselves, we cannot, should not flinch away. For Jung, coming to terms with the Shadow, although initially lonely and alarming, is the necessary path to consciousness, a binding together of a divided self that gives the strength to unload the heavy burdens of morality, idealism, passivity and conformity. In confronting the Shadow we turn towards the true ideal of an individual in a dynamic, unfixed constantly evolving state of individuality and freedom; enabling a state of becoming rather than a stagnation of merely being in this world.

Sanctae offers the viewer a profoundly emotional experience of female identity, which can be felt by viewers regardless of their gender. It acts as an awakening to the experience of being woman, visualizing the very real experiences of woman ordinarily concealed. In encountering the differences in Rucquoi’s imagery, we are armed with the tools to uncover the experiential truths of being. In response, we develop awareness of the potential to become whole, to become more than merely an other.